Between Editions: From Green Cards to Handcuffs.

How Immigration Enforcement Is Being Rewritten

ICE and Homeland Security Investigations police make an arrest outside an immigration court in Phoenix. Photo: Ross D. Franklin/AP file

To mark the holiday season and as a gift to all my discerning readers, here is yet another Between Edition story, free for all to read. No subscription required. (Although subscribing would be deeply appreciated.) ¡Feliz Navidad y próspero Año Nuevo!

For many immigrant families, the path to legal status was once built on a simple assumption: that engaging with the system — showing up to court, attending interviews, filing paperwork — was a step toward stability, not a risk in itself. That assumption is now quietly collapsing.

Across the country, routine green card interviews have begun ending not with approvals or follow-up notices, but with handcuffs. Immigration lawyers describe a growing pattern in which applicants appear before U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services seeking to legalize their status and instead are taken into custody by Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Federal offices that were long treated as neutral spaces are increasingly experienced as enforcement traps.

In San Diego, immigration attorney Jan Bejar recounts to The New York Times a case that captures the shift. His client, married to a U.S. citizen, had overstayed a tourist visa after entering the country as a child. He followed the rules, filed the paperwork, and attended his interview. USCIS approved the green card petition the same day ICE arrested him.

A similar story unfolded in Cleveland, where attorney Courtney Koski’s client was arrested during a marriage-based interview in late November. She had lived in the United States for 25 years, brought as a child by her parents. A missed court hearing years earlier left her with a removal order she barely understood at the time. Her green card petition was approved. She remains in detention.

“He’s suffering without his wife during the holidays,” Koski told The Times of her client’s husband. “She’s being punished for trying to do the right thing.”

The American Immigration Lawyers Association has documented dozens of such cases nationwide, though ICE and USCIS have not released official figures. According to people familiar with internal procedures, some USCIS offices now alert ICE when interviews involving flagged cases are nearing completion, allowing agents to act immediately.

USCIS officials defend the policy on legal grounds: overstaying a visa is a violation that can lead to deportation. Former asylum officer Michael Knowles, now a union leader representing USCIS employees, argues the issue is not legality but discretion — when, where, and how enforcement power is exercised.

An Ideology That Reaches Beyond the Border

But to see these arrests as isolated enforcement choices misses the deeper shift underway. What is happening inside green card interview rooms is not an aberration. It is the operational expression of a broader ideological turn at the top of the Trump administration.

Stephen Miller, one of President Trump’s closest advisers and the architect of much of his immigration policy, has been increasingly explicit about how he views immigration — not as a legal process with an endpoint, but as a generational threat. In recent appearances, Miller has argued that immigration problems do not end with the first generation. They persist, he says, through children and grandchildren, producing what he describes as permanent patterns of welfare dependence, criminality, and failed assimilation.

This claim is not new in American history, but it is newly central to federal policy. It echoes the rhetoric of early-20th-century restrictionists who justified the National Origins Act of 1924 by arguing that immigrants from southern and eastern Europe were biologically and culturally incapable of becoming Americans. That logic was later discredited not by theory but by lived reality: the children and grandchildren of those immigrants became some of the country’s most economically successful and socially integrated citizens.

Contemporary data tells a similar story. Study after study shows that children of immigrants learn fluent English, achieve higher levels of education than their parents, and experience upward mobility over time. These patterns have held consistently for immigrants arriving since the 1960s. Economically, immigrants and their descendants tend to contribute more than they consume. Socially, they assimilate not instantly, but steadily.

From Rhetoric to Practice

Yet Miller’s argument rejects that arc entirely. In his framing, immigration does not lead to integration; it reproduces failure. People are not evaluated as individuals, but as carriers of inherited dysfunction. Belonging is no longer something one earns over time. It is something granted at birth — or not at all.

That worldview matters because it reshapes how policy is implemented. If immigration is seen as a permanent cultural threat, then discretion becomes a liability. Legal processes become suspect. Compliance itself becomes evidence of vulnerability rather than good faith. A green card interview is no longer a step toward resolution; it is an opportunity to remove someone who should never have been allowed to stay in the first place.

This logic also underpins the administration’s push to end birthright citizenship. While there is no legal basis to revoke citizenship from U.S.-born children of immigrants, the argument advanced by Miller and others is not really about constitutional text. It is about redefining membership. It asks whether American identity is something people can grow into — or something the state can withhold indefinitely, even from those born on U.S. soil.

Public opinion has shifted in ways that make this argument politically potent. Trump returned to office amid widespread frustration over large-scale arrivals during the Biden years, which strained local resources and tested public patience. The administration has responded by tightening both legal and illegal immigration pathways, halting naturalization from certain countries under new travel bans, and dramatically expanding detention.

The Vanishing Off-Ramp

What gets lost in the politics is how these choices change behavior. Lawyers report that fear is now altering decision-making across immigrant communities. People who may be eligible to adjust their status hesitate to file. Others skip interviews. Some abandon valid asylum claims simply to avoid prolonged detention. When engagement with the legal system becomes dangerous, the system stops functioning as intended.

This is not merely about enforcement being harsher. It is about the disappearance of an off-ramp. Immigration policy once operated on the premise that, however imperfectly, there was a path from undocumented status to lawful presence to citizenship. That premise is eroding. In its place is a system that treats time, family ties, and compliance as irrelevant — or even incriminating.

The green card interview arrests and the generational rhetoric are not separate stories. They are the same story, told at different levels. One shows how ideology filters down into practice. The other shows how practice reinforces ideology. Together, they mark a profound shift in how the United States defines who belongs.

The result is an immigration system no longer oriented toward resolution, but toward exclusion — not just of newcomers, but of the idea that becoming American is possible at all.

The Immigrant Foundation of American Science

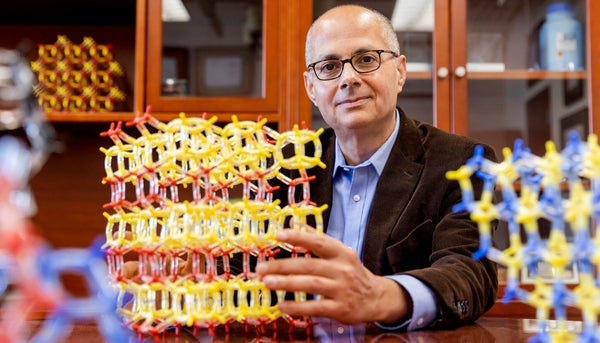

Omar Yaghi with molecular models of some of his porous structures. Photo by Brittany Hosea-Small for UC Berkeley

For decades, immigrants have been central to U.S. scientific dominance. Many came seeking opportunity or refuge, eventually winning Nobel Prizes decades after arrival. Their discoveries built industries that reshaped global life — from nuclear physics to the digital revolution.

The list is long. Leo Esaki from Japan, Ivar Giaever from Norway, Herbert Kroemer from Germany, and Willard Boyle from Canada all conducted their Nobel-winning research in the United States. Their work on quantum mechanics and semiconductors laid the foundation for modern electronics — the chips that power everything from phones and cars to satellites and medical devices. Those breakthroughs created millions of jobs and trillions of dollars in wealth, much of it clustered in Silicon Valley.

That pattern has repeated across generations. The same openness that drew Einstein and Fermi also attracted new generations of scientists from Asia, Europe, and Latin America. By welcoming them, the United States not only advanced human knowledge but embedded itself at the heart of the global scientific network.

Dr. Omar Yaghi’s story reflects that tradition. Born in Amman, Jordan, he grew up scrambling for water in a city where taps ran only every week or two. Years later, that experience inspired his research on metal-organic frameworks, or MOFs — crystalline structures capable of storing gases and even pulling moisture from desert air. His lab’s prototype water harvester, tested in California’s Mojave Desert, produced nearly three cups of pure drinking water a day.

“That discovery would not have happened if I didn’t have that background,” he told The Walll Street Journal. “Mixing talent helps us solve big problems.”

A Narrower Pipeline

In recent years, however, the flow of such talent has slowed. A steep new fee on research visas was introduced to “incentivize” domestic hiring, while foreign students have faced lengthy background checks and unpredictable delays. For many universities, the bureaucracy has become a barrier to recruiting the world’s best minds. “We used to compete globally for brilliance,” said one senior academic administrator. “Now we’re competing with our own paperwork.”

The administration argues that U.S. science can thrive without immigrants. Vice President J.D. Vance told Newsmax earlier this year that the country need not “import a foreign class of servants and professors,” framing the crackdown on student visas as a chance for Americans to “really flourish.” Stephen Miller, the chief architect of Trump’s immigration agenda, went further, claiming that America’s mid-20th-century dominance occurred during a period of low immigration — proof, he said, of “our own genius.”

Historians counter that claim. The scientific surge of that era, they note, was driven by immigrant physicists and mathematicians fleeing war-torn Europe. Felix Bloch, Emilio Segrè, Maria Goeppert Mayer, Eugene Wigner, and Hans Bethe — all immigrants — won Nobels for research conducted at U.S. institutions. Their discoveries shaped the nuclear age and underpinned the nation’s Cold War technological edge.

“This kind of thing is a gift and not something we should take for granted,” said Doug Rand, a former White House science official who now helps immigrant researchers find work. “We should make things easier, not harder.”

The Risk of Self-Isolation

The irony, economists say, is that America’s scientific ecosystem was itself a byproduct of globalization. The same open channels that allowed foreign students to study, stay, and innovate also helped launch U.S. companies that dominate the global economy. Limiting that flow could undercut the very prosperity the administration hopes to protect.

Dr. Yaghi worries that closing the pipeline will make it harder for the United States to compete with rising scientific powers such as China, where state funding and industrial policy are fueling rapid progress in artificial intelligence, clean energy, and biotechnology. “Scientists should be seen as an investment in a country’s future,” he said. “If we slip, others will pass us.”

The broader impact may unfold slowly but decisively. Fewer international collaborations mean fewer breakthroughs; fewer foreign students mean fewer start-ups and patents. Over time, the intellectual gravity that once pulled talent toward the U.S. could shift elsewhere — toward nations that remain open, ambitious, and well funded.

For now, the debate reflects two starkly different visions of what makes America exceptional. One sees strength in self-reliance and national preference; the other in the exchange of ideas that transcends borders. The first builds walls to preserve opportunity. The second builds bridges to expand it.

As Dr. Yaghi’s work — turning molecules into water — depends on connectivity, on the invisible bonds that hold structures together. The same is true, he said, of science itself. “When we mix perspectives, we create something stronger than any single piece on its own,” he noted. “That’s the secret of progress — and of America’s success.”

###